One of the most fascinating discoveries I’ve made in working on my memoir is the Detská encyclopédia, published in Czechoslovakia first in the early 60s and re-issued in the early 80s. Author Říha was director of the State Publishing House for Children’s Literature from the late 50s (right after the show trials died down) through 1967, just before the Prague Spring, but he became part of the leadership of “normalized” Czechoslovakia after the Warsaw Pact invasion—all of which is to say, he probably was a true believer in the red dawn. The encyclopedia he penned for children is charmingly written, lavishly illustrated, and laced with all kinds of good moral instruction—and a few well-placed threats—for the youth of the socialist tomorrow. Here are my own translations of a few of my favorite entries…

Read moreBarefootery

In recognition of National Go Barefoot Day, here’s my testimony to having my own two feet planted firmly on the ground!

First things first: our culture is really weird about shoelessness. I would say it’s the last taboo, but there are, thank God, a few more left in place. Let’s say it’s the last taboo of zero moral significance. Americans, and probably North Atlantic/Westerners generally, equate shoes with civilization. To have no shoes is to be poor, destitute, uneducated, probably stupid, and maybe pregnant. Twice I believe myself to have been mistaken for a prostitute, once in the U.S. and once in Germany, because, despite my definitely not sexy attire, I was out in public shoeless…

Read moreThree Memoirs of Slovak Communism

There’s nothing to put American political vagaries in radical context like reading a whole bunch of books about communism. My string of Slovak novels in English has had to give way for awhile to piles and piles on the twentieth century’s strangest political experiment, not to say the bloodiest. I must admit, having grown up on Cold War rhetoric on the American side and having not a few issues with the runaway consumerism of this society, I had been inclined to think it was ever so slightly possible that communism was not as bad as Reagan and his predecessors had made it out to be.

I was wrong. It was worse…

Read moreTwelve Brothers and a Thirteenth Sister

Ľudovít Fulla, “Twelve Brothers and a Thirteenth Sister,” at Galéria Nedbalka

As I’ve been working on my memoir and making better acquaintance with Slovak literature, I’ve also discovered Slovak fairy tales. There are analogs to the British/French/German fairy tale tradition that Americans are more familiar with—a Rumpelstiltskin-type story, a Tom Thumb, a Cinderella (but also a Cinderel or “Ashboy”). There are definitely distinctives, too, like making Jesus or even the Heavenly Father a character in the tale, and above all the abiding passion for the tátoš or fairy horse. What has delighted me most, though, is this story, “Twelve Brothers and a Thirteenth Sister.” It was a favorite of nineteenth-century Slovak feminists, who appreciated the very unusual plot device of a girl rescuing a whole bunch of helpless, bewitched, and hedged-in boys. Eat your heart out, Sleeping Beauty! …

Read moreReading “Silence” on My First Visit to Japan

I have known about Silence for a long time, and its basic plot, and deliberately avoided it because it seemed too painful to bear. But on our first trip to Japan, amidst the beautiful cherry blossoms in full bloom and warm welcome by our future colleagues, I decided I was ready to brave it. I am glad I did...

Read moreSlovak Novels in English #5: Don’t Cry for Me

If Judy Blume had been Slovak, this would be the result.

At first blush, it’s a pretty straightforward young adult novel. Told in the first person, the story is the stream-of-consciousness narration of fourteen-year-old Olga, who lives in Bratislava with her parents and Granny. She endures all the straightforward troubles of early adolescence: the romance that is desired but withheld or lost set in contrast with the repulsive advances of the undesirable; parents who don’t understand and yet are desperately loved and needed all the same; friends who are sometimes devoted and sometimes unreliable; school stresses; emotional highs and lows that pass through the soul unannounced like a gale-force wind...

Read moreCan French Food Be Cooked Outside of France?

Julia Child says yes. I say no.

Back when I was still in graduate school and living on a considerably severer budget than I am now, I did not buy cookbooks. Instead, I got them out of the library and typed up any recipes I thought I might like to fit when printed on an index card. Actually, this is not a bad strategy, if you don’t count the loss of valuable time in typing. I still vet potential cookbook purchases at the library.

Anyway, I ran across a reference to a revered French cookbook, Bistro Cooking by Patricia Wells...

Read moreSlovak Novels in English #4: The Ugly

This is a “Slovak novel in English” in a rather different sense from the ones I’ve discussed so far. The author is a Slovak national, and the hero is a Slovak—though of an imaginary tribe of Siberian Slovaks who got tired of capturing that vast snowscape at the end of World War I, got off the trans-Siberian railroad, and stayed put in an idyllic valley called Verkhoyansk—though, according to Business Insider, the real valley of Verkhoyansk is “the most miserable place in the world,” which makes it for sure a genuine choice of oppressed peasantry...

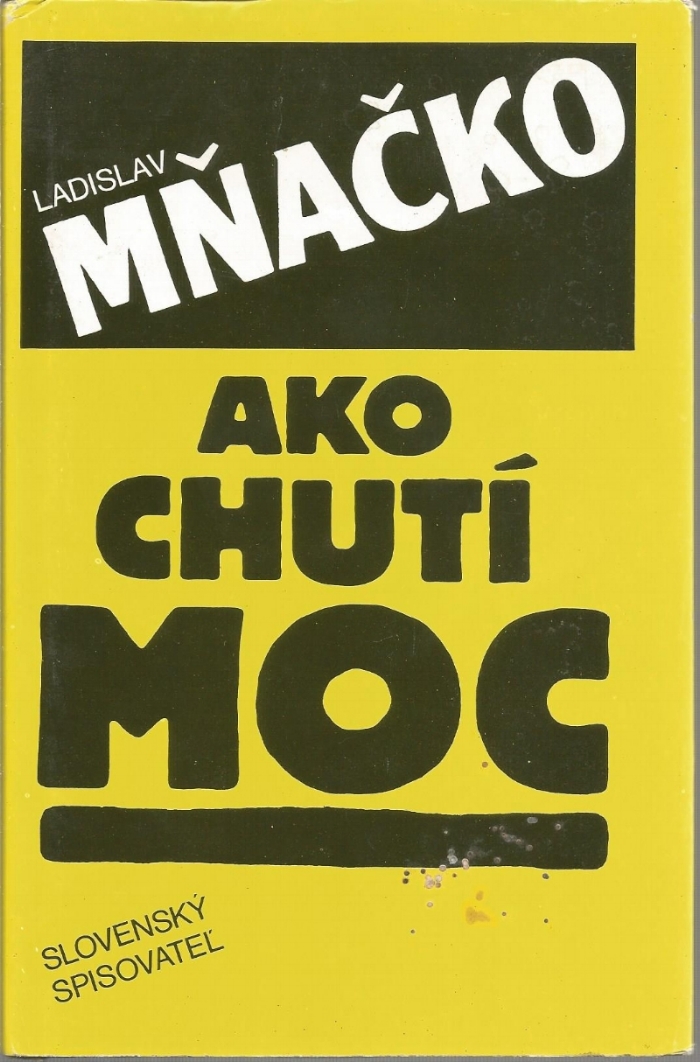

Read moreSlovak Novels in English #3: The Taste of Power

Ladislav Mňačko did not start out as a critic of communism. Quite the contrary, he was supportive of the regime change in Czechoslovakia in 1948 and looked forward to all the ways Marxism would transform human society and personality for the better, working as a journalist to document the change from the old ways of greed, theft, and exploitation to the new era of solidarity and sharing. Except… things didn’t turn out that way...

Read moreIn Memoriam Ursula K. Le Guin

Photo Credit: William Anthony/The Nation, also in Neil Gaiman's obituary of Le Guin

On some level I had been expecting the news for awhile, as she was born in 1929, but it still saddened me terribly to hear of Ursula K. Le Guin’s death. Few other writers have made such an impact on me. This may come as a bit of a surprise from a theologian, since Le Guin did not hide her disdain for Christianity (or, I am tempted to say, what she thought of as Christianity). She was, if anything, a philosophical Taoist. But it is a rare and precious thing to discover a thinker from whom you benefit as much by disagreement as by affinity...

Read more